Ageless Questions: Revisiting Sontag’s "On Women" and the enduring tyranny of beauty

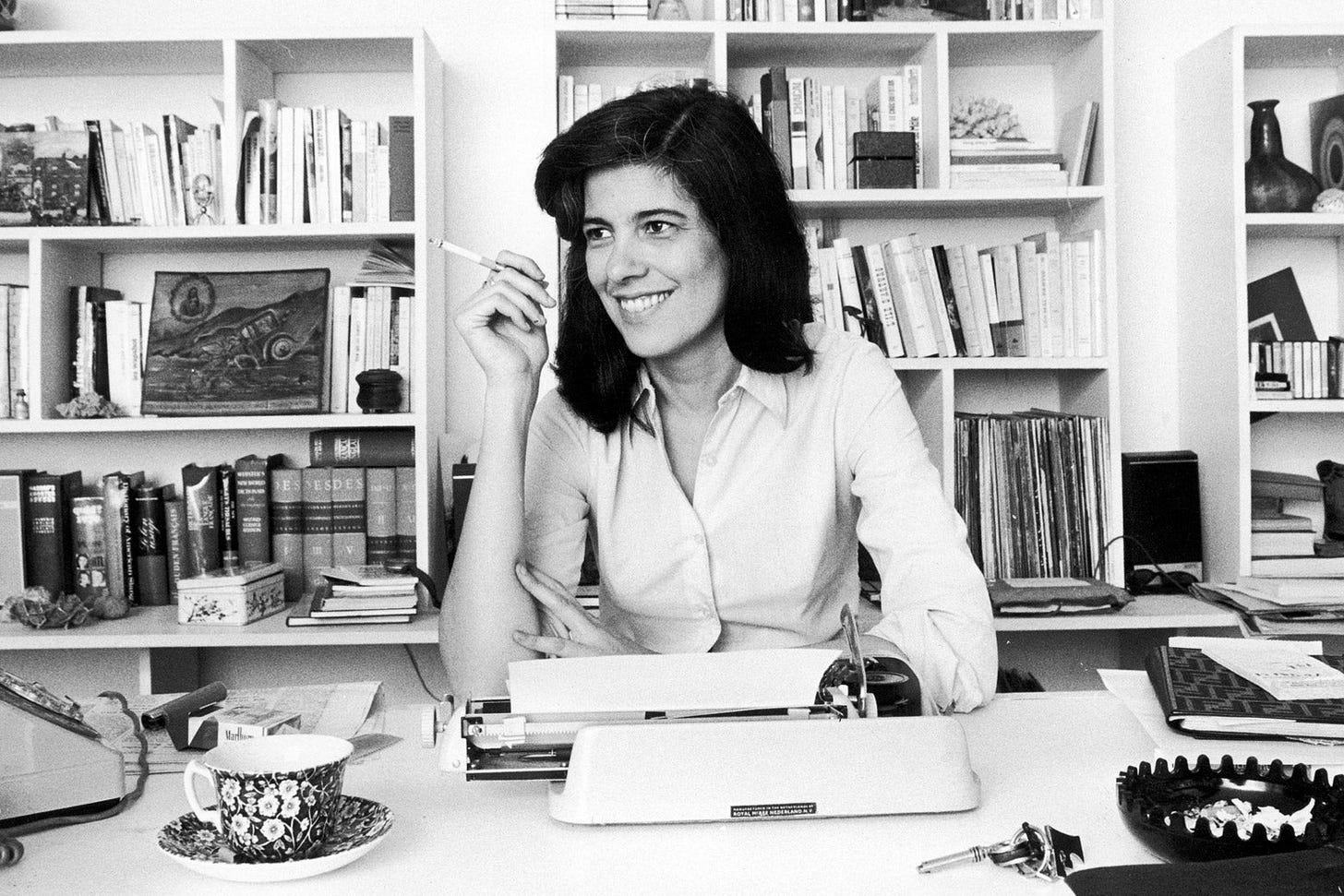

Why Susan Sontag’s sharp take on ageing and beauty still -sadly- rings true decades later

Susan Sontag’s On Women is a collection of essays as fierce as it is thought-provoking, offering a dissection of gender politics that is both unflinchingly honest and elegantly argued.

In her essays she takes on the grim reality of society's obsession with youth and beauty, drawing a stark line between the pressures on men and women as they grow older.

One of the greatest tragedies of each woman’s life is simply getting older; it is certainly the longest tragedy. Aging is a movable doom. It is a crisis that never exhausts itself, because the anxiety is never really used up.

Her wit shines through as she traces how, for women, ageing is a liability rather than the “distinguished” upgrade society grants men.

For man there is no equivalent to the humiliating condition of being an old maid, a spinster

For Sontag, these beauty standards are a form of tyranny, trapping women in a relentless pursuit of an impossible ideal, and the sad irony is that her words, penned in the ’70s and ’80s, still resonate painfully today.

Beauty is of course a myth. The question is, what sort of myth. In the past two centuries, it has been a myth imprisoning to women — because it is exclusively associated with them. The idea of beauty that we inherit was invented by men and is still largely administered by men. It is a system from which men scrupulously have exempted themselves.

Her insight feels surprisingly modern, almost unsettlingly so. We may have made strides in gender equality, but the beauty industry still commands billions, and social media has only amplified the pressures she decried.

To be a woman is to be an actress. Being feminine is a kind of theatre, with its appropriate costumes, décor, lighting, and stylised gestures. (…) Mothers tell their daughters (but never their sons): You look ugly when you cry. Stop worrying. Don’t read to much.

Women are still sold youth as a currency, ageing as a curse, while men are granted the grace to “distinguish” as they silver.

The essays are, therefore, both a reflection and a forecast, hinting at a beauty culture that is all too familiar to readers today. Yet there is an encouraging shift. Conversations about beauty standards are louder, with a growing rejection of ageism and a push for genuine inclusivity in media. But Sontag's question – how will it change next? – is still pressing. It’s a shame that so many of her arguments remain as pertinent today as they were when she wrote them, underscoring how deeply embedded these double standards are in our society.

In reading On Women, I found myself once again captivated by Sontag’s eloquence, by her ability to blend philosophy with the everyday experience. But there's an undeniable sadness in revisiting these essays decades later and recognising the familiar. This collection, both vital and unsettling, reminds us that while progress has been made, we are still unfortunately navigating many of the same issues.

Men have a greater range of behaviour available to them than women have, and they have considerably more mobility in the world. (Simply consider the fact that in most places she might go in the world, a woman alone risks rape or physical violence. Basically, a woman is only safe at home or when protected by a man.)